Comparative pathogenesis of Fusarium spp. obtained from diseased chickpea plants in Morocco

DOI:

https://doi.org/10.55779/nsb15311361Keywords:

Fusarium sp., leaf lesion, pathogenicity, root rot, varieties of chickpeasAbstract

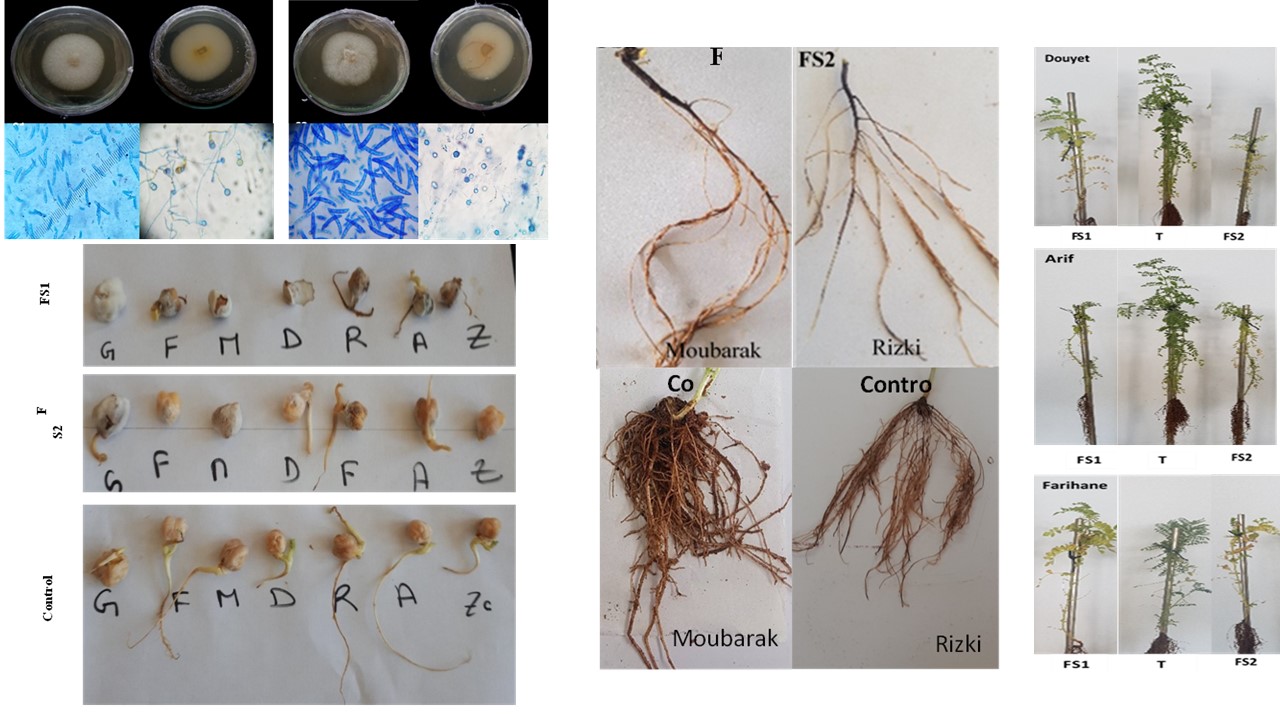

The pathogenicity of two isolates (FS1 and FS2) of the Fusarium solani isolated from diseased chickpea plants harvested from two different regions from Morocco, which were identified morphologically and molecular, was evaluated as the severity, incidence and index of the disease. The results show that the two isolates tested were able to induce symptoms in both parts of the plant (root and aerial), of the seven chickpea varieties (‘Garbanzo’, ‘Farihane’, ‘Moubarak’, ‘Douyet’, ‘Rizki’, ‘Arifi’ and ‘Zahour’), which were associated with a reduction in all measured agronomic parameters. However, the intensity of the symptoms depends on the combination of the variety and the isolate of Fusarium. It appears that the FS2 isolate affected the ‘Moubarak’ variety much more, while the pathogenicity of the FS2 isolate was more pronounced on the ‘Rizki’ variety. The increase in the leaf damage index as a function of time is due to the evolution of leaf yellowing through several physiological stages (necrosis, stunting, wilting, leaf fall), before causing plant death. At the end of the experiment, the re-isolation of the two Fusarium isolates from the four vegetative parts of all inoculated varieties was positive.

Metrics

References

Aboul-Soud MAM, Yun BW, Harrier LA, Loake GJ (2004). Transformation of Fusarium oxysporum by particle bombardment and characterization of the resulting transformants expressing a GFP. Mycopathologia 158:475-482. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11046-005-5370-7

Ahmed S, Melkamu A (2006). Chickpea, lentil, grass pea, fenugreek and lupine disease research in Ethiopia. In: Ali K, Kenneni G, Malhorta R, Génial S, Makkouk K, Halila NH (Eds). Food and forage legumes of Ethiopia progress and prospects. ICARDA, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia pp 215-220.

Asif M, Rooney LW, Ali R, Riaz MN (2013). Application and opportunities of pulses in food system: a review. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition 53(11):1168-1179. https://doi.org/10.1080/10408398.2011.574804

Bekele D, Tesfaye K, Fikre A, Cook DR (2021). The extent and association of chickpea Fusarium wilt and root rot disease pressure with major biophysical factors in Ethiopia. Journal of Plant Pathology 103(2):409-419. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42161-021-00779-4

Bekkar AA (2007). Variability in morphology and pathogenicity in Fusarium oxysporum Schelcht. Emend. Snyd. & Hans. f. sp. Ciceri (Padwick), agent of vascular wilt of chickpea (Cicer arietinum L.). MSc Dissertation, University of Mascara, Mostafa Istanbul, Algeria, pp 92.

Belabid L, Fortas Z, Dalli D, Khiare M, Amdjad D (2000). Wilt and root rot of lentils in north-western Algeria. Cahiers Agricultures 9(6):515-518.

Bodah, ET (2017). Root rot diseases in plants: a review of common causal agents and management strategies. Agricultural Research & Technology 5(3):555661. https://doi.org/10.19080/ARTOAJ.2017.04.555661

Beniwal SPS, Ahmed S, Gorfu D (1992). Wilt/root rot diseases of chickpea in Ethiopia. In: Beniwal SP, Ahmed SM, Gorfu D (Eds). Wilt/root rot diseases of chickpea in Ethiopia. International Journal of Pest Management 38:48-51. https://doi.org/10.1080/09670879209371644

Boureghda H (2009). Investigation of the antagonistic effect of Trichoderma spp. against Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. ciceris (Padwick) Matuo and K. Sato (Foc), agent of chickpea wilt. PhD Thesis, National Agronomic Institute –El Harrach, pp 11.

Bouznad Z, Solh M, Labdi M, Rouibah M, Tebbal H (1990). Preliminary results on the causes of wilt and root rot of chickpea in Algeria. In the 8th congress of the Mediterranean phytopathological union. Agadir-Morocco, pp 345-346.

Champion R. (1997). Identifying seed-borne fungi. Revue Suisse de Viticulture, Arboriculture et Horticulture, INRA, Paris, pp 398.

Chang YC, Baker R, Kleifeld O, Chet I (1986). Increased growth of plants in the presence of the biological control agent Trichoderma harzianum. Plant Disease 70:145-148. http://dx.doi.org/10.1094/PD-70-145

Chliyeh M, Msairi S, Ouazzani Touhami A, Benkirane R, Douira A (2017). Detection of Fusarium solani as a pathogen causing root rot and wilt diseases of young olive trees in Morocco. Annual Research & Review in Biology 13(5):1-7. http://dx.doi.org/10.9734/ARRB/2017/33744

Cunnington J, Lindbeck K, Jones RH (2007). National diagnostic protocol for the detection of fusarium wilt of chickpea (Fusarium Oxysporum f. sp. ciceris). Plant Health Australia, Camberra, Australia.

Dixit GP, Srivastava AK, Singh NP (2019). Marching towards self-sufficiency in chickpea. Current Science 116:239-242. http://dx.doi.org/10.18520/cs/v116/i2/239-242

Domsch KH, Gams W, Anderson TH (1980). Compendium of soil fungi. Volume 1. Academic Press (London) Ltd.

Doyle JJ, Doyle JL (1987). A rapid DNA isolation procedure from small quantities of fresh leaf tissues. Phytochemical Bulletin 19:11-15.

Dubey SC, Singh B (2004). Reaction of chickpea genotypes against Fusarium osysporum f. sp. ciceri causing vascular wilt. Indian Phytopathology 57:233.

El-Aoufir A (2001). Study of vascular wilt of chickpea (Cicer arietinum) caused by Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. ciceri. Evaluation of the reliability of isoenzymatic analysis and vegetative compatibility for the characterization of physiological races. PhD Thesis, Laval University, pp 161.

FAOSTAT (2019). Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), Statistics Division (FAOSTAT). Retrieved 2020 June 15th from: http://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#data/QC/visualize

Fayaz A, Hakim K, Rifat A, Ijaz A (2014). Growth rate of different isolates of Fusarium solani, the cause of root rot of okra (Abelmoschus esculentus L.). Asian Journal of Agriculture and Biology 2(2):114-118.

Gardes M, Bruns T (1993). ITS primers with enhanced specificity for Basidiomycetes- application to the identification of mycorrhizae and rusts. Molecular Biology 2:113-118. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-294X.1993.tb00005.x

Greaney FJ, Machacek JE, Johnston CL (1938). Varietal resistance of wheat and oats to root rot caused by Fusarium culmorum and Helminthosporium sativum. Scientific Agriculture 18(9):500-523.

https://doi.org/10.4141/sa-1938-0021

Gupta OM, Khare MN, Kotasthane SR (1986). Variability among six isolates of Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. ciceri causing vascular wilt of chickpea. Indian Phytopathology 39(2):279-281.

Halila MH, Strange RN (1996). Identification of the causal agent of wilt of chickpea in Tunisia as Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. ciceris race 0. Phytopathologia Mediterranea 35:67-74.

Halila I, Benyoussef NO, Ksia MB, Kharrat M (2014). Field evaluation of different recombinant breed populations of chickpea resistant to Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. ciceris. In: Annales de l'INRAT 87:43-62. Institut National de la Recherche Agronomique de Tunisie (INRAT).

Halila I, Rubio J, Millán T, Gil J, Kharrat M. Marrakchi M (2010). Resistance in chickpea (Cicer arietinum) to Fusarium wilt race '0'. Plant Breeding 129(5):563-566. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1439-0523.2009.01703.

Halila I, Cobos MJ, Rubio J, Millán T, Kharrat M, Marrakchi M, Gil J (2009). Tagging and mapping a second resistance gene for Fusarium wilt race 0 in chickpea. European Journal of Plant Pathology 124(1):87-92. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10658-008-9395-x

Haware MP, Nene YL, Natarajan M (1996). Survival of Fusarium oxysporum f. sp ciceris. Plant Diseases 66:809-810.

Haware MP, Nene YL, Rajeshwari R (1978). Eradication of Fusarium oxysporum f. sp ciceris transmitted in chickpea seed. Phytopathology 68:1364-1367.

Haware MP, Nene YL (1980). Influence of wilt at different stages on the yield loss in chickpea. Tropical Grain Legume Bulletin 19:8-40.

Haware MP (1988). Fusarium wilt and other important disease of chickpea in the Mediterranean area. Proceedings of international Workshop on present status and future prospects on chickpea crop production and improvement in the Mediterranean countries. CIHEAM/EEC, Agrimed/ICARDA. Zaragoza, Spain. 11-13.

Haware MP (1990). Fusarium wilt and other important diseases chickpea in the Mediterranean area. Options Mediterranean Serie A: Seminars Mediterranean 9:61-64.

Honnareddy N, Dubey SC (2006). Pathogenic and molecular characterization of Indian isolates of Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. ciceris causing chickpea wilt. Current Science 91(5):611-666.

Jendoubi W, Bouhadida M, Boukteb A, Béji M, Kharrat M (2017). Fusarium wilt affecting chickpea crop. Agriculture 7(3): 23. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture7030023

Jeon CS, Kim GH, Son KI, Hur JS, Jeon KS, Yoon JH, Koh YJ (2013). Root rot of balloon flower (Platycodon grandiflorum) caused by Fusarium solani and Fusarium oxysporum. The Plant Pathology Journal 29(4):440. https://doi.org/10.5423/PPJ.NT.07.2013.0073

Jha UC, Chaturvedi SK., Bohra A., Basu, PS, Khan MS, Barh D (2014). Abiotic stresses, constraints and improvement strategies in chickpea. Plant Breeding 133(2):163-178. https://doi.org/10.1111/pbr.12150

Jimenez Diaz RM, Castillo P, Jimenez Gasco MM, Landa BB, Navas Cortes JA (2015). Fusarium wilt of chickpeas: biology, ecology and management. Crop Protection 73:16-27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cropro.2015.02.023

Jimenez-Gasco MDM, Milgroom MG, Jimenez-Diaz RM (2004). Stepwise evolution of races in Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. ciceris inferred from fingerprinting with repetitive DNA sequences. Phytopathology 94:228-235. https://doi.org/10.1094/PHYTO.2004.94.3.228

Jiminez-Gasco MM, Jiminez-Diaz RM (2003). Development of a specific polymerase chain reaction-based assay for the identification of Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. ciceris and its pathogenic races 0, 1A, 5 and 6. The American Phytopathological Society 2:200-209. https://doi.org/10.1094/phyto.2003.93.2.200

Jukanti AK, Gaur PM, Gowda CLL, Chibbar RN (2012). Nutritional quality and health benefits of chickpea (Cicer arietinum L.): a review. British Journal of Nutrition 108:11-26. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0007114512000797

Kaloki P, Devasirvatham VKY, Tan D (2019). Chickpea abiotic stresses: combating drought, heat and cold. In: Abiotic and Biotic Stress in Plants. IntechOpen. https://doi.org/10.5772/intechopen.83404

Kistler HC, Bosland PW, Benny U, Leong S, Williams PH (1987). Relatedness of strains of Fusarium oxysporum from crucifers measured by examination of mitochondrial and ribosomal DNA. Phytopathology 77:93.

Koike ST, Kirkpatrick SC, Gordon TR (2009). Fusarium wilt of strawberry caused by Fusarium oxysporum in California. Plant Disease 93(10):1077-1077. https://doi.org/10.1094/PDIS-93-10-1077A

Laamari A, Bentaibi A, Fadlaoui A, Al Balghitti A, Dahan R, Badraoui I, Aden A (2016). Actors in the legume value chain in Rencontres Francophones Legumineuses. France-Dijon, 28.

Lee O, Koo H, Yu JW, Park HY (2021). Genotyping-by-sequencing-based genome-wide association studies of Fusarium wilt resistance in radishes (Raphanus sativus L.). Genes 12(6):858. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes12060858

Machehouri A, Ben Messaoud B, Nassiri L, Ibijijen J (2017). Enumeration of natural populations of chickpea Rhizobium (Cicer arietinum) in different soils of Morocco. European Scientific Journal 13(6):273.

Martínez-Atienza J, Jiang X, Garciadeblas B, Mendoza I, Zhu JK, Pardo, JM, Quintero FJ (2007). Conservation of the salt overly sensitive pathway in rice. Plant Physiology 143(2):1001-1012. https://doi.org/10.1104/pp.106.092635

Mbofung GCY, Pryor BM (2010). A PCR-based assay for detection of Fusarium oxysporum f.sp. lactucae in lettuce seed. Plant Disease 94:860-866. https://doi.org/10.1094/PDIS-94-7-0860

McGovern RJ (2015). Management of tomato diseases caused by Fusarium oxysporum. Crop Protection 73:78-92. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cropro.2015.02.021

Merga B, Haji J (2019). Economic importance of chickpea: production, value, and world trade. Cogent Food & Agriculture 5:1615718. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311932.2019.1615718

Messiaen CM, Cassini R (1968). Fusarium Disease Research. IV Systematics of Fusarium. Annals of Epiphyties 19(3):387-454.

Messiaen CM, Blancard D, Lafon R, Rouxel F. (1991). Les maladies des plantes maraîchères. Les maladies des plantes maraîchères, pp 1-568.

Michielse CB, Rep M. 2009. Pathogen profile update: Fusarium oxysporum. Molecular Plant Pathology 10:311-24. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1364-3703.2009.00538.x

Morjane H, Harrabi M (1995). Detection and analysis of genetic variation in chickpea by genetic fingerprinting. Review of INAT 10(1):65-73.

Murray MG, Thompson WF (1980). Rapid isolation of high molecular weight plant DNA. Nucleic Acids Research 8:4321-4325. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/8.19.4321

Navas Cortes JA, Hau B, Jimenez Diaz RM (2000). Yield loss in chickpea in relation to development of Fusarium wilt epidemics. Phytopathology 90:1269-1278. https://doi.org/10.1094/PHYTO.2000.90.11.1269

Navas Cortes JA, Lan da BB, Rodriguez Lopez J, Jimenez Diaz RM. 2008. Infection by Meloidogyne eartiellia does not break down resistance to races 0, 1A and 2 of Fusarium oxysporum f. sp ciceris in chickpea genotypes. Phytopathology 98:709-718. https://doi.org/10.1094/PHYTO-98-6-0709

Navas-Cortés JA, Hau B, Jiménez-Díaz RM (1998). Effect of sowing date, host cultivar, and race of Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. ciceris on development of Fusarium wilt of chickpea. Phytopathology 88(12):1338-1346. https://doi.org/10.1094/PHYTO.1998.88.12.1338

Nelson PE, Toussoun TA, Marasas WFO (1983). Fusarium species: an illustrated manual for identification. University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press.

Nene YL, Haware MP, Ready M (1979). Diagnosis of some chickpea (Cicer arietinum). ICRISAT Information Bulletin 3:1-44.

Nene YL, Reddy MV (1987). Chickpea diseases and their control. In: Sexena MC, Singh KB (Eds). The Chickpea. Wallingford, UK: CAB International, pp 233-370.

Nirina R, Zananirina J, Ramamonjisoa D, Ramanankierana H (2014). Lutte biologique antifongique : actinomycètes du sol rhizosphérique antagonistes de Fusarium isolé du fruit de tomate (Solanum lycopersicum L., 1753) pourri. Afrique Science 10(3):243-255.

Nucci M, Anaissie E. (2007). Fusarium infections in immunocompromised patients. Clinical Microbiology Reviews 20(4):695-704. https://doi.org/10.1128/cmr.00014-07

Ounane SM, Irekti H, Bacha F (2003). Study of the effect of water stress on nitrogen fixation and biomass in chickpea (Cicer arietinum) inoculated with different strains of Mesorhizobium ciceri. The conferences. DHS. INRA. Paris. 100:69-80.

Pande S, Narayana RJ, Sharma M (2007). Establishment of the chickpea wilt pathogen Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. ciceris in the soil through seed transmission. Plant Pathology Journal 23(1):3-6. http://dx.doi.org/10.5423/PPJ.2007.23.1.003

Rafiq CM, Mahmoud MT, Ahmad M, Ali I, Kaukab S, Shafiq M, … Iqbal U (2020). Fusarium wilt’s pathogenic studies and disease management: A review. Genetics and Molecular Research 19:Gmr16039974.

Rahim AM, Aziza KD, Tarabeih AM, Hassan AAM (1992). Damping-off and root rot of okra and table beet with reference to chemical control. Assiut Journal of Agricultural Sciences 23:19-36.

Raju S, Jayalakshmi SK, Sreeramulu K (2008). Comparative study on the induction of defense related enzymes in two different cultivars of chickpea (Cicer arietinum L.) genotypes by salicylic acid, spermine and Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. ciceri. Australian Journal of Crop Science 3:121-140.

Rakotoarimanga N, Zananirina J, Ramamonjisoa D, Ramanankierana H (2014). Antifungal biological control: rhizospheric soil actinomycetes antagonists to Fusarium isolated from rotten tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L.) fruit. Africa Science: International Journal of Science and Technology 10(3).

Reddy MV, Singh KB (1984). Evaluation of a world collection of chickpea germ plasm accessions for resistance to Ascochyta blight. Plant Disease 68(10):900-901.

Roy F, Boye JI, Simpson BK (2010). Bioactive proteins and peptides in pulse crops: pea, chickpea and lentil. Food Research International 43:432-442. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodres.2009.09.002

Sghir F, Touati J, Chliyeh M, Mouria B, Selmoui K, OuazzaniTouhami A, … Douira A (2016). Effect of Trichoderma harzianum and endomy-corrhizae on growth and Fusarium wilt of tomato and eggplant. World Journal of Pharmaceutical and Life Sciences 2(3):69-93.

Shah TS, Babar MA, Iqbal JM, Ahsanul MH (2009). Screening of chickpea (Cicer arietinum) induced mutants against Fusarium wilt. Pakistan Journal of Botany 4:1945-1955.

Sharma DK, Muehlbauer FJ (2007). Fusarium wilt of chickpea: physiological specialization, genetics of resistance and resistance gene tagging. Euphytica 157:1-14. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10681-007-9401-y

Sharma M, Ghosh R, Tarafdar A, Rhatore A, Ghobe DR, Kumar AV, … Harer PN (2019). Exploring the genetic cipher of chickpea (Cicer arietinum L.) through identification and multi-environment validation of resistant sources against Fusarium wilt (Fusarium oxysporum f. sp ciceris). Frontiers in Food Systems 3:78. https://doi.org/10.3389/fsufs.2019.00078

Sharma M, Sengupta A, Ghosh R, Agarwal G, Tarafdar A, Nagavardhini A, … Varshney RK (2016). Genome wide transcriptome profiling of Fusarium oxysporum f. sp ciceris conidial germination reveals new insights into infection related genes. Scientific Reports 6:37353. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep37353

Solh MB, Halila HM, Hernandez-Bravo G, Malik BA, Mihov MI, Sadri B (1994). Biotic and abiotic stresses constraining the productivity of cool season food legumes in different farming systems: specific examples. In: Muehlbauer FJ, Kaiser WJ (Eds). Current Plant Science and Biotechnology in Agriculture Book. Expanding the Production and Use of Cool Season Food Legumes 19:209-230.

Srivastava AK, Chaturvedi SK, Singh NP (2017). Genetic base of Indian chickpea (Cicer arietinum L.) varieties revealed by pedigree analysis. Legume Research 40:22-26. http://dx.doi.org/10.18805/lr.v0iOF.3550

Srivastava AK, Dixit GP, Singh NP, Saxena DR, Saabale PR, Raghuvanshi KS, Anandani VP (2021). Evaluation of chickpea (Cicer arietinum L.) accessions for Fusarium wilt resistance. Journal of Environmental Biology 42:82-89. http://doi.org/10.22438/jeb/42/1/MRN-1475

Sunkad G, Deepa H, Shruthi TH (2019). Chickpea wilt: status, diagnostic and management. Indian Phytopathology 72:619-627. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42360-019-00154-5

Thudi MA, Chllikineni A, Liu X, Ha W, Roorkiwal M, Yang W, Jian J, Doddamani D, Gaur PM, Varshney RK (2016). Recent breeding programs enhanced genetic diversity in both desi and kabuli varieties of chickpea (Cicer arietinum L.). Scientific Reports 6:38636. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep38636

Tivoli B. (1988). Identification guide of the different species or varieties of Fusarium encountered in France on the potato and in its environment. Agronomie. EDP Sciences 8(3):211-222. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10658-020-02177-5

Trapero-Casas A, Jimenez-Diaz RM (1985). Fungal wilt and root rot diseases of chickpea in southern Spain. Phytopathology 75:1146-1151.

Upasani ML, Limaye BM, Gurjar GS, Kasibbatla SM, Joshi RR, Kadoo NY, Gupta VS (2017). Chickpea Fusarium oxysporum interaction transcriptome reveals differential modulation of plant defense strategies. Scientific Reports 7:7746. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-07114-x

Van Der-Maessen LJG (1987). Origin, history and taxonomy of chickpea. In: Saxena MC, Singh KB (Eds). The Chickpea. Pp 11-37.

Voisin AS, Salon C, Munier-Jolain N, Bertrand N (2002). Effect of mineral nitrogen on nitrogen nutrition and biomass partitioning between the shoot and roots of pea (Pisum sativum L.). Entomologia Experimentalis et Applicata 103(3) :239-248. https://doi.org/10.1023/A.

Westerlund J, Campbell RN, Kimble KA (1974). Fungal root rots and wilt of chickpea in California. Phytopathology 64: 432-436.

White TJ, Bruns T, Lee S, Taylor J (1990). Amplification and direct sequencing of fungal ribosomal RNA for phylogenetics. In: MA Innes, DH Gelfand, JJ Sninsky, TJ White (Eds). PCR protocols. A guide to methods and applications, Academic Press, Inc., San Diego, California pp 315-322. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-372180-8.50042-1

Zemouli-Benfreha F, Djamel-eddine H, Merzoug A (2014). Fusarium wilt of chickpea (Cicer arietinum L.) in North-West Algeria. African Journal of Agricultural Research 9(1):168-175. https://doi.org/10.5897/AJAR2013.6694

Downloads

Published

How to Cite

Issue

Section

License

Copyright (c) 2023 Naila ELHAZAT, Manal ADNANI, Fadoua BERBRER, Said BOUGHRIBIL, Najoua MOUDEN, Azeddine ERRIFI, Mohamed CHLIYEH, Karima SELMAOUI, Rachid BENKIRANE, Amina OUAZZANI TOUHAMI, Allal DOUIRA

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Papers published in Notulae Scientia Biologicae are Open-Access, distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution License.

© Articles by the authors; licensee SMTCT, Cluj-Napoca, Romania. The journal allows the author(s) to hold the copyright/to retain publishing rights without restriction.

License:

Open Access Journal - the journal offers free, immediate, and unrestricted access to peer-reviewed research and scholarly work, due SMTCT supports to increase the visibility, accessibility and reputation of the researchers, regardless of geography and their budgets. Users are allowed to read, download, copy, distribute, print, search, or link to the full texts of the articles, or use them for any other lawful purpose, without asking prior permission from the publisher or the author.

.png)